What's Happening at Discovery Diving

Get all the latest info from our Instructors and Staff on our SCUBA Classes, Charters, Equipment and Special Events.

Underwater Aircraft Carriers?

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 2855

- 0 Comments

- Subscribe to this entry

- Bookmark

There wouldn't seem to be many good reasons for designing a submarine to launch airplanes, but during the past one hundred years at least six countries have experimented with the concept some with surprising success.

Germany was first to try in 1915 when a floatplane pilot teamed up with a U-boat captain he'd met socially and flew his aircraft off the sub's deck. Since it was an unsanctioned trial no follow up flights were made.

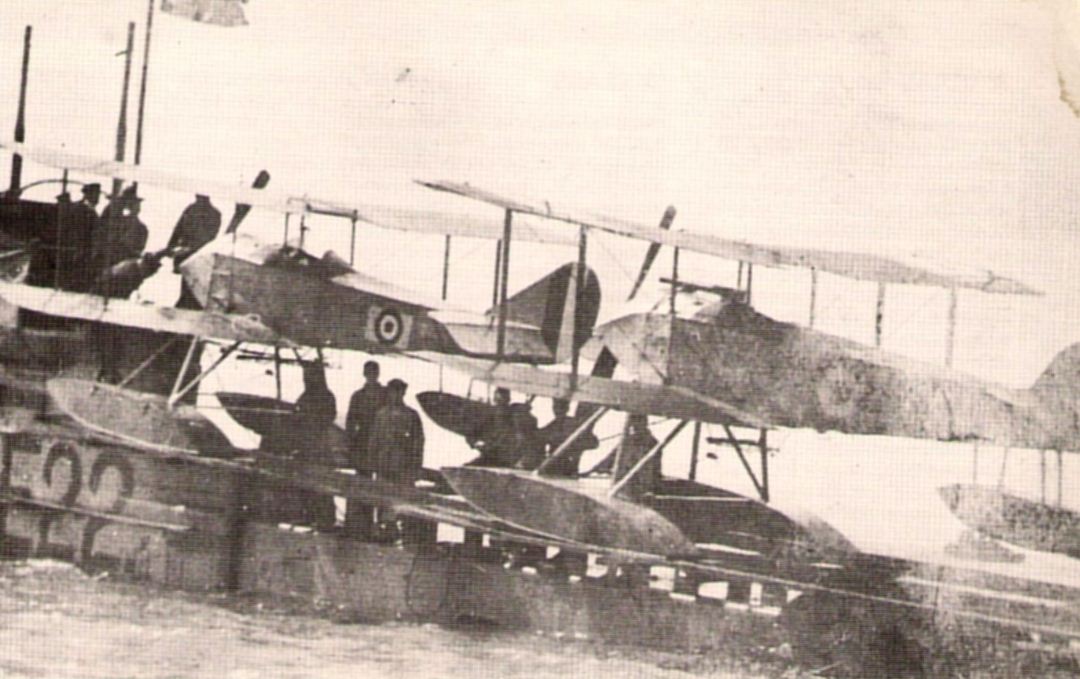

The English were next to try when the HMS E-22 launched two Sopwith Schneider seaplanes from her deck in April 1916 (see photo below). The experiment was not repeated, however, after the E-22 was sunk two days later by a German U-boat.

The United States didn't begin its own sub-plane experiments until 1923 when the S-1 carried a Martin MS-1 biplane in a small on-deck storage container. Unfortunately, it took sixteen man hours to assemble the aircraft, which made the idea impractical since the longer a sub remains on the surface the more vulnerable she is to attack.

The first submarine fully capable of carrying, launching, and retrieving an airplane was Britain's M-2 (see photo below). Unfortunately, her Parnall Peto floatplane had difficulty landing in more than a light breeze--a non-starter for a sub operating in the North Sea. But the M-2 also suffered from a fatal design flaw which wasn't discovered until the sub vanished one morning in January 1932.

The M-2 was eventually found three miles off the coast of England in one hundred feet of water. Her hangar door, which was located too close to the sub's waterline, was open as was a hatch leading from the hangar into the sub. Presumably, the M-2 was accidentally flooded causing her sixty man crew to perish along with England's desire for further experimentation with plane-carrying subs.

Germany, Great Britain, the United States, Italy, and France all investigated some kind of sub-plane combination with poor results. It wasn't until Japan picked up the gauntlet that the concept bore fruit. Subs played an important scouting role in the Imperial Japanese Navy, which saw them as a means of locating and destroying an enemy fleet before it reached their island nation. Since a sub-launched floatplane could significantly increase a sub's scouting range, Japan spent the next twenty years perfecting the combination.

Starting with a Heinkel seaplane purchased from Germany in 1923, Japan rapidly progressed to the I-7 and I-8, the first Japanese subs built from scratch with a catapult and water tight deck hanger. By December 7, 1941, Japan had 11 plane-carrying submarines deployed at Pearl Harbor with three times that number under construction.

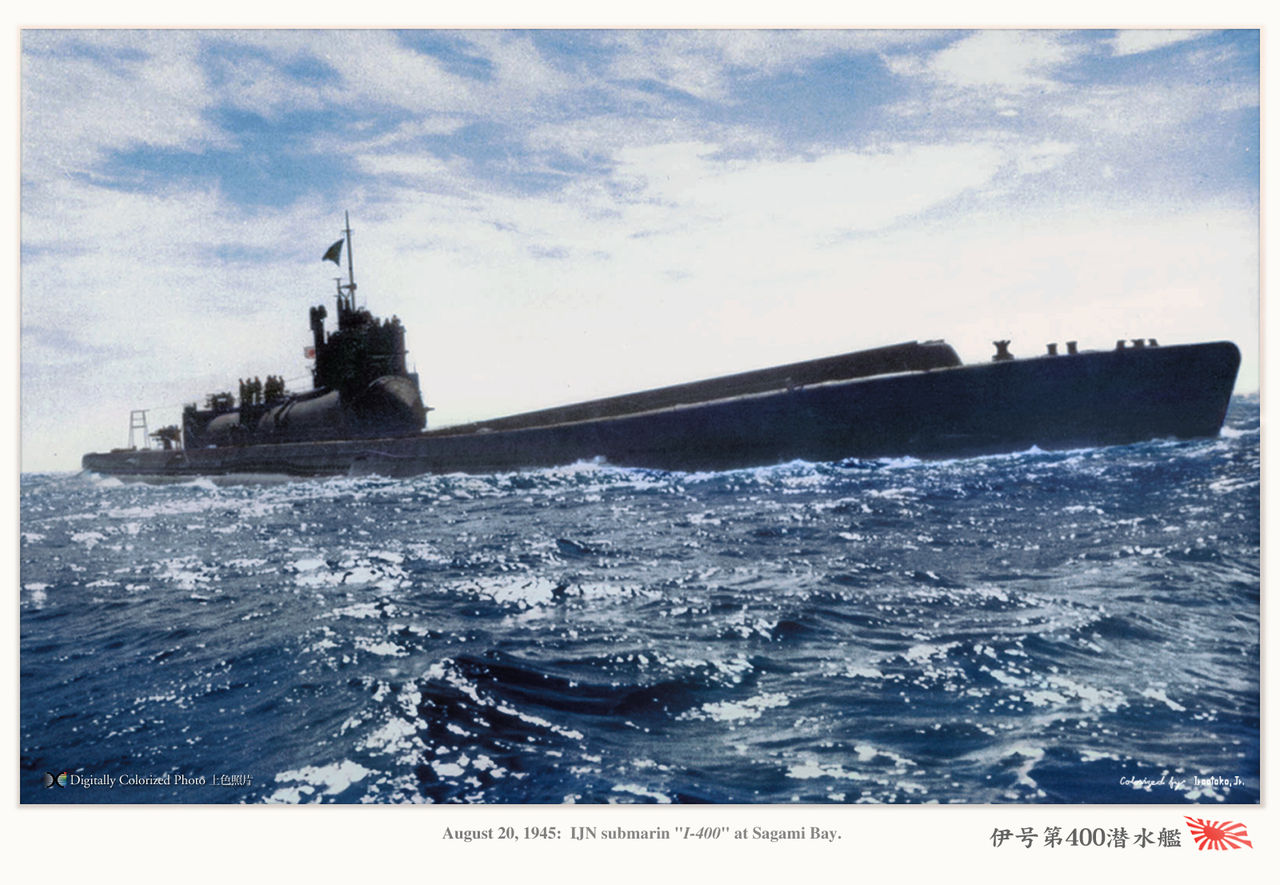

But it wasn't until Admiral Yamamoto developed Japan's I-400 class submarine as a follow up to his attack on Pearl Harbor that the ultimate achievement in underwater aircraft carriers was realized.

Over 400 feet in length, the I-400s were the largest submarines ever commissioned until the Ethan Allen class in 1961. Purpose-built to launch a surprise aerial attack against New York City and Washington, D.C, each sub could travel one and a half times around the world without refueling, and carried three Aichi M6A1 attack planes in a water tight deck hangar (see photo below).

My new, non-fiction book, Operation Storm: Japan's Top Secret Submarines and Its Plan to Change the Course of World War II, recounts the little known story of the I-400 subs from conception to deployment. But people hearing about these subs for the first time often find the story too incredible to be true. Sub-launched airplanes? Underwater aircraft carriers? It sounds more like an episode from the old sci-fi series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (which boasted its own flying sub) than anything Japan might undertake.

But Japan's I-400 subs were actually built, launched, and commissioned. In fact, they were on their way to complete their mission when the war ended. Even then, the I-401, the squadron's flagship, refused to surrender, went rogue, and almost triggered a resumption of hostilities.

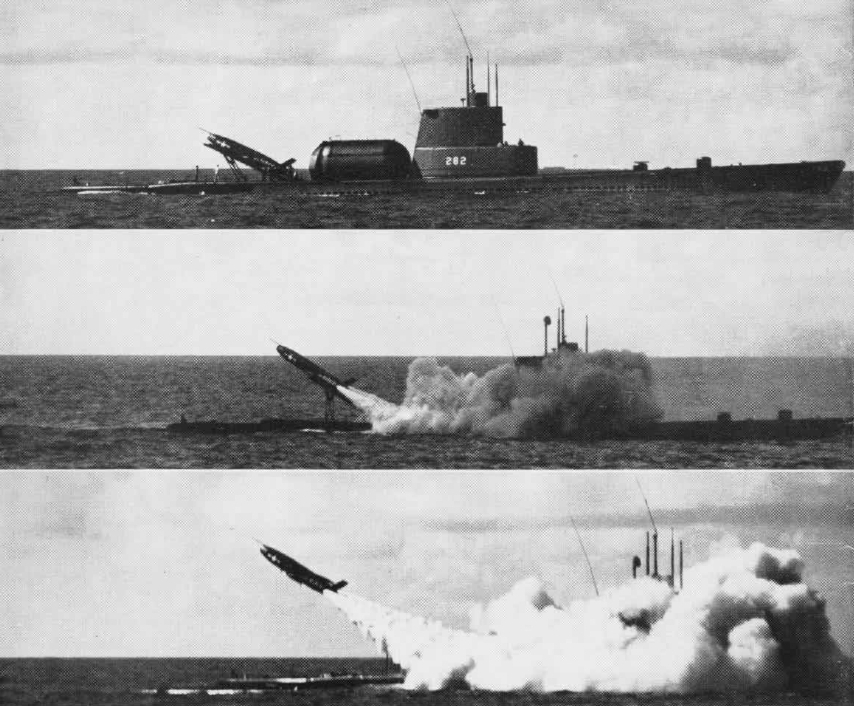

After World War II ended, the United States sailed two of the I-400 subs from Tokyo to Pearl Harbor for further study. As a result, the Regulus missile program, which launched nuclear-tipped missiles from a surfaced sub's water-tight deck hangar (see photos below), owes a debt to the I-400s. The Douglas Aircraft Company, which designed an attack plane that could be housed and launched from a Regulus sub's missile hangar, owes a similar tip of the hat.

In fact, Japan's realization that a submarine could be used to launch an offensive attack against an enemy's city is the same strategy our sub-based nuclear deterrent relies upon today. In other words, airplane-carrying subs may be a relic from the past, but their legacy continues sixty years later making them not such a crazy idea after all.